The little crocodile book reviews

Grammar enthusiast. Cat lover. Illustrator. Slytherin. Loki's Army. Spending a lot of time reading the world. And fanfiction. .

Actually at: www.thelittlecrocodile.com

The Gracekeepers is a gentle and beautiful work of dystopian speculative fiction that doesn’t so much advance with a bang as with a whimper.

Set in a far-off dystopian future, the world of The Gracekeepers is dominated by water, with land a scarce commodity (think Waterworld). The wealthy minority live on land, while the rest – the ‘damplings’ – have to make do living on ships and boats. The story follows North, a girl who performs with a great bear on a travelling circus boat; and Callanish, a gracekeeper who lives in isolation on a manmade island, performing burials at sea for dead damplings. When the two girls meet, they find in one another the companionship that they’ve been searching for their whole lives.

‘You didn’t hear? The landlockers at the last island were gossiping. Some baby born with webbed fingers and great gaping gills on its throat. They buried it alive at their World Tree – said it was some wicked spell cast by damplings, the curse of the sea. The curse of us, North. It’s only a matter of time before they tire of damplings and try to bury the whole cursed lot of us. Get yourself a foot on land before that happens.’

‘I don’t want to be one of them, Bero. There are more important things than full bellies.’

‘Are there? I’m not so sure.’ Bero tensed his left shoulder, moving the empty sleeve pinned up on his shirt. ‘We fell into a hard life here. Imagine what we could do if we weren’t hungry all the time.’

I enjoyed The Gracekeepers, but some parts of it did feel a bit slow or flat. While most of it is written from the perspective of North or Callanish, there are also a lot of chapters written from the point of view of the other characters, which helps to give the story more depth. At the same time, I didn’t feel that the characters were adequately complex. Part of this I’m sure stems from the tranquil voice of the writing – big events do happen (for example the storm in the first half of the book), but the gentle tone of the narrative, which others have described as being lyrical or poetic, tends to dull their impact, flattening out any extremities.

Despite this, the book did draw me in – gently, gently – and reading it was a pleasure.

The story is engaging, if not particularly fast paced, and there are a lot of satisfying ideas present within it – not-so-subtle references to people having destroyed the world, with the flooded cities of the past visible beneath the ocean, and themes of class segregation and religion (not in the best light) are also there. One of my favourite lines of the book is:

It looked clean enough to Flitch – but then, maybe religion made you see dirt where no one else could.

I’ve also seen a lot of people compare this to The Night Circus (by Erin Morgenstern), which I’m ashamed to say I’ve had lying around my house since the week of its release sometime in 2011, completely unread.

I should also tag that old trigger warning about animal cruelty onto this book. Part of the gracekeeper’s job is to assign a grace, a small bird bred specifically for this purpose, to every dead body. The grace is kept in a cage without food or water, and when it dies the grieving period for that person is complete. The practice certainly adds to the feel of the book and to Callanish’s character (as she gives the birds small mercies, such as a few grains of food), so it does serve a purpose in the story and hopefully won’t put you off reading it.

Overall, The Gracekeepers makes for a contemplative, gentle read, with likeable characters and an imaginative setting. (Not to mention the stunning cover!)

I received a copy of this book via Netgalley in exchange for an honest review.

Editions of The Gracekeepers will be released 23 April 2015 by Harvill Secker and 19 May 2015 by Crown.

Cute and light slash story, out Tuesday!

A high school romantic drama that’s easy to read and relate to – I really enjoyed it and got through the whole thing before teatime.

The story is told by Simon, a ‘not-so-openly gay’ sixteen-year-old whose secret falls into the hands of a classmate when he leaves himself logged into his email on a school computer. Before long he finds himself blackmailed into playing wingman for class clown Martin in order to keep his sexual identity under wraps and protect the privacy of ‘Blue’, the boy he’s been emailing. And with Blue becoming increasingly flirtatious online, Simon is desperate to find out the boy’s true identity – he knows it’s someone at his school, but who?

Simon vs the Homo Sapiens Agenda had me enthralled from the off:

It’s a weirdly subtle conversation. I almost don’t notice I’m being blackmailed.

We’re sitting in metal folding chairs backstage, and Martin Addison says, “I read your email.”

“What?” I look up.

“Earlier. In the library. Not on purpose, obviously.”

– Chapter 1

The characters are introduced very quickly and naturally, which instantly makes you feel at home with them and lets you fall into the story; this is narrated by Simon in a cute and light style, and features some of the correspondence between him and Blue, the anonymous boy he’s been getting closer to via email. The dialogue is well-written and funny, and the characters diverse and believable.

While some serious ideas are approached – the most obvious example being expectations of the norms in society, for instance, heteronormativity and white normativity – these are dealt with within the context of the story. No one suddenly gets murdered for holding a certain view to make a literary point. This is a book about kids set in a high school, and the consequences are realistic.

The story’s main focuses are identity and friendship, with Simon gradually coming to realise that he isn’t the only one changing and that there’s a lot about his friends and family that he doesn’t know.

I also liked the many cultural references within the book, which range from Assassin’s Creed to Elliott Smith (Waltz #2 is particularly excellent) to yaoi to fanfiction (Drarry all the way), instantly making the whole experience more engaging. Speaking of that last item, I would recommend this book to readers of slash fanfiction – the characters are very easy to get into, and the style is reminiscent of some well-written examples of FF that I’ve read in the past. (In fact, I’d be interested in knowing whether Albertalli has ever dabbled in fanfiction!)

I also liked that this wasn’t quite the same story that you tend to get with high school drama, i.e. Person A deceiving Person B, then falling for them, then Person B finding out and all hell breaking loose. While there was still a fairly standard structure to the story, it never approached the sort of cringe-worthiness that is quite common to the genre. This book knows what it wants to be and it fills its shoes very well.

Fluffy and light with the ultimate message that people are all different and that we could all do with paying more attention to one another, Simon vs the Homo Sapiens Agenda is well-written and fun; highly recommended for fans of the genre (and fanfic aficionados!).

Simon vs the Homo Sapiens Agenda will be available to buy from 7 April 2015. I received an advance copy of this book via Netgalley in exchange for an honest review.

This is easily one of the best fantasy books I have read in the past few years.

When thirteen-year-old Delphine and her parents relocate to Alderberen Hall to join a strange and elite society for the ‘perpetual improvement of man’, she is immediately suspicious. Within minutes of entering the estate, Delphine overhears a conversation that has her convinced the society is a front for some nefarious plot to facilitate an invasion (by communists? Germans?!) into England. But, before long, the true intent of the league is revealed and it is nothing quite so pedestrian…

The style of the writing is wonderfully fluid and the descriptions, the turns of phrase that Clare uses are spot on without being clichéd, often conveying a feeling of a sinister foreshadowing.

Mother stood in the middle of a chequered marble floor, like the last piece in a chess game

…

A figure stood in the doorway. He was soaked through; his trousers shone like sealskin. His shirt was nearly transparent, save for thick arterial creases lining his arms.

The phrasing reflects a poet’s observation and makes each sentence a pleasure to read, something that holds true for the dialogue as well. Particularly enjoyable are the interactions between Delphine and Mr Garforth, and the professor’s awkwardness and dialogue also quickly make you grow fond of him.

‘There was a scout.’

Mr Garforth looked up. ‘Were you spotted?’

‘I killed him,’ she said. ‘It.’

He raised his wispy eyebrows. ‘What range?’

‘Sixty yards.’ She caught his frown. ‘Fifty. Forty. I hid the body.’

‘Good girl.’

She set her gun down by the stove. ‘What’s for dinner?’

A spider was scuttling across the table. He slammed his palm on it, scooped it up and popped it into his mouth.

‘You’re not funny.’

He unfurled his fist, revealing the spider, unharmed. Delphine frowned to disguise a smile.

– from the first chapter of The Honours

Delphine is an insatiably curious and impish protagonist, easy to like and constantly keeping the action moving. Frequently dismissed by the adults at Alderberen Hall, she spends her days in espionage, trying to discover the society’s secrets. The young heroine comes across as a little unstable at times, eager for glory and obsessed with guns and combat, but the reality is that she’s alone amidst a clique of strangers and adults who don’t so much ignore as overlook her completely.

What should be noted is that this isn’t a gritty realist novel.

The characters, while sure of themselves and vividly portrayed, are just that – characters. This isn’t a bad thing, by any means: I for one enjoy a book that is comfortable in its incarnation. I only mention this because, looking at a couple of other reviews of The Honours, I want you to know what sort of story you’re in for here. There will be dirt and grit and blood, and there will be thrilling escapades. Personally, I adored every minute and it only racks up excellence as it hurtles on, like a daring ball of adventure tearing down Fantasy Hill.

I have seen The Honours heralded as ‘one of the most exciting pieces of fantasy fiction in recent years’, and this is far from a generous assessment. The book is simply a pleasure, through and through.

Well-paced and richly painted, Clare’s debut lives up to the hype and I can only hope that we can expect more content of this calibre in the future.

The Honours is available to buy as of today, 2 April 2015. I was send an ARC of this book in exchange for an honest review.

If you were making a documentary about Arcadia, where would you travel to? If you were looking for happiness, how would you start? The Age of Magic follows a film crew seeking to document just this. But along their journey they must each confront their own demons as well as a nightmare that they’ve conjured together: Malasso.

This is a book about the search for truth, happiness, and the power of emotion and experience to alter perception.

They were on the train from Paris to Switzerland when the white mountains and the nursery rhythms of the wheels lulled him to sleep. He found himself talking to a Quylph.

‘What are you afraid of?’ it said.

‘Why should I be afraid of anything?’ Lao replied.

‘Maybe you are afraid of Malasso?’

‘Why should I be afraid of him?’

‘Everyone else is.’

– The Age of Magic, Ben Okri, p. 9

The work is separated into ‘books’ of short (normally page-long) chapters that read more like stanzas of elegant free verse that regular narrative. The language and rhythm is poetic, and the content matches this with the inclusion of fantastic entities – fae folk, daughters of Pan, spirits, demons. The story is the philosophical pursuit of happiness, framed by magic realism. And it will make you remember and reflect on who you really are.

The language of the book has clearly been carefully chosen and, about three-quarters into it, the ideal and unmarred style of the writing began to grate on me. There is no vulgarity, no dirt to the text – it is untarnished by the crudeness of real life. Even while it talks about ‘eviling’, it remains ideal and fantastic – a work of aestheticism, a book that isn’t pretending not to be a book. It is worth knowing this from the off, because chances are you know what you like and what you don’t in terms of style, and this can be a deal breaker. I still very much enjoyed it, however – the only real points at which it bothered me were during the book’s two very briefly described sex scenes, which had me quirking one eyebrow and saying ‘seriously?’. (Part of the problem here may have been that Okri is a man attempting to describe a woman’s experience of sex. He didn’t nail it.)

Reading The Age of Magic, you get the impression that it is greatly autobiographical, a collection of clear and simply expressed insights that Okri has, at one time, realised for himself and is now trying to share with you. Many of these will be ideas that the reader has had themselves, but which have been forgotten with the passing of the moment. The train at the start of the book is the instant in which you have these slight but significant revelations – but you must always get off the train and, in doing so, forget your small epiphany and carry on with ‘real life’. As Lao notes in precisely such a moment: ‘Just when I’m beginning to understand something, we always arrive.’

You get the feeling that Okri is trying to make you aware of all these moments in your past, as well as lead you through those that he has experienced – a task that is immediately problematic. As Okri himself writes, ‘books should be lived to be read’ – that is, you can only truly understand something through first-hand, personal experience. This makes The Age of Magic a sort of enigma. Okri is well aware that all the small realisations, all the ideas that he puts forward through his characters cannot simply be assimilated by the reader. Instead, he is trying to direct the reader’s attention to the discovery of these things; he is using ‘the power of the devil to serve the sublime’.

In this sense, the book seems to acknowledge our generation’s focus on devouring complex ideas through bite-size TV segments, articles, tweets – things that can teach one the wisdom of centuries in one afternoon. But there is no way to skip to enlightenment without the aching, gradual experience of living through it; without personal meaning and relevance.

One such realisation is that of the difficulty of actually hearing and understanding another person – ‘It’s easier to be clever than to listen’, one character asserts; ‘We hear best in recollection.’ (Which calls to mind Wordsworth’s proclamation of poetry as ‘the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity’.) Another, expressed in Book 1, is the idea of home, a sense of self and comfort with who you are, with the train journey seeming to represent the self as it travels through life and experiences everything that it passes. Yet another, and my personal favourite term of the book, is the concept of ‘eviling’ in Book 2 – that is, falling into a resentful outlook that makes you see the ugliness in the people around you, makes you focus on it. In this mood, the main character, Lao, is afraid even to look at his partner, Mistletoe, because he doesn’t want to corrupt his perception of her.

What I found particularly interesting here is the way in which one character is able to snap out of their eviling by wandering mutely through a train station, surrounded by foreign words to which they have no claim. In this state of anonymity they lose themselves, both their established idea of who they are and the perception of who they are by those around them; similarly, the objects around them lose their names and are seen anew, thus returning to their Platonic ideals. I think the idea appealed to me because it is exactly what one becomes acutely aware of during life drawing – the figure you draw can easily become distorted if you don’t constantly study it yourself because, instead of looking at it, you end up merely remembering what you know a body to look like. Instead of seeing you are working on an assumption. The message you end up learning is the same as that in Okri’s passage: you must learn to study, to experience, to see for yourself the world around you in order to find the truth in it. It is this thought that jerks the character out of their eviling.

I also enjoyed the fact that Lao and his companions go through different moods, which make them argue and act badly, but that this doesn’t make them any less themselves: a person is capable of changing their mood and, equally, their perception.

There are dozens of such ideas woven through the text of The Age of Magic, and it does make for a beautiful tapestry. Pick up this book if you are looking for some gentle insight into the pursuit of happiness, some elegant morsels of philosophy and a little bit of magic.

All quotes, other than the Wordsworth one, are from The Age of Magic. I was sent a copy of this book in exchange for an honest review.

An anthology of ‘science fiction, fantasy and strange stories’ from Liars’ League, Weird Liesbrings together a broad range of styles and themes in an array of delectable morsels. It is well written, well edited and, most importantly, consistently engaging – in short it is an absolute pleasure to read, from cover to cover.

Each story stands alone and is, frankly, just pretty darn good. I love being handed a book that I’ve not heard of before (I was sent this through Goodreads’ First Reads, so didn’t know exactly what to expect) and finding that it is this good. The fact that the stories cover a lot of different topics and take on many different styles also makes the reading of it all rather inspiring. If you’re keen on writing yourself, I would heartily recommend this book as well as good anthologies in general (for more inspiration try stories by Donald Barthelme, and prose poetry by Simon Armitage and Luke Kennard).

Among my favourite Weird Lies are ChronoCrisis 3000, which takes the form of an instructional letter from a scientist to a time traveller; Let There Be Light, a story about two people in a dark world; Free Cake, a meditation on explosive workplace stress;Touchdown, a ghost story; Zwo, on monsters; Daphne Changes, metamorphosis with a general Apollo; The Love Below, in which a boy struggles to keep his feet on the ground;Candyfloss, of dreams and nightmares…

Damn, I only wanted to list two or three and, really, I could go on.

Weird Lies is an excellent anthology and if you’re feeling like reading something a little different, something that you can’t just compartmentalise into a handful of genres, then I suggest you grab this. I’m certainly planning to pick up a few of their other collections, which can be found on their site as well as Amazon.

Liars’ League itself also sounds like a rather interesting organisation.

In a sense, fiction is a lie; acting is lying too. And so the League brings together the best liars we can find – actors and authors – to tell great, brand new stories. It seems to be working, because we were recently featured in The Guardian’s list of the 10 best storytelling nights in the UK.

Writers write. Actors read. Audience listens. Everybody wins.

The League holds monthly fiction nights during which actors read out new short stories written by people the world over. Their events are held at The Phoenix pub (which is incidentally a really cool venue that also hosts an excellent weekly comedy night) in Cavendish Square, London, and the readings are filmed and uploaded to YouTube as well as a free podcast. Their online archive contains more than 300 stories.

This was also the first I’d heard of Arachne Press, the publishers of Weird Lies, but they seem pretty cool. Others must agree since they’ve won various awards for their books, which include short-story anthologies, poetry and young adult novels. They also hold workshops and readings – you can find out more about these on their blog.

Weird Lies includes stories by Alan Graham, Alex Smith, Angela Trevithick, Andrew Lloyd Jones, Barry McKinley, C. T. Kingston, Christopher Samuels, David McGrath, David Malone, David Mildon, Derek Ivan Webster, Ellen O’Neill, James Smyth, Jonathan Pinnock, Joshan Esfandiari Martin, Lee Reynoldson, Lennart Lundh, Maria Kyle, Nichol Wilmor, Peng Shepherd, Rebecca J. Payne, Richard Meredith, Richard Smyth and Tom McKay.

Thank you to the editors and Goodreads for sending me this book through Goodreads’ First Reads

1

1

‘Stories are the truth beyond the flat, stone world,’ he says. ‘There’s more fire inside the engine than the wheels. That’s what it is.’

‘I’m cold,’ I say.

‘The world turns on its axis, but people turn on their souls. Things you can’t see, boy, support what you can.’

‘We tell stories to fly, you said.’

‘I did.’

Is he proud of me? I hope so. I want him to be.

When Oli is uprooted from his home in London and taken on an impromptu vacation to stay at his aunt and uncle’s house, he is confused. Why did they have to leave so suddenly and to visit a relative whom he has never met? Why is his mother acting so nervous, what is she hiding? And where is his dad?

Despite what his family tells him, Oli knows this isn’t just a regular vacation; something has happened, something big, and no one wants him to find out what it is. But that isn’t the only strange thing.

There’s also Eren.

Eren, the strange, dark creature with the hoarse voice and ragged wings. Eren, that lives in this house, in the hatch above Oli’s bed. Eren, that’s always watching, always whispering…

The book is about stories and about their power.

I find it difficult to find fault with Eren, which so much reminded me of David Almond’sSkellig as well as Neil Gaiman’s writing style when I first started it, but which asserted its own presence quickly and enveloped me within its stories, always so many stories. The book is very well written and really engaging, to the point that I can confidently say that it didn’t bore me for a moment; I was never tempted to put the book down and go and do something else. And it isn’t only for children; as the preface is quick to tell you:

This is a story about storytelling.

It’s not for children any more than it’s for adults. This is a story for readers and dreamers – for people who know that there’s a wolf in every story and darkness in every dream, just as much as there are heroes and magic.

There are also illustrations in the book, which is always a welcome touch – more books need pictures, in my opinion. These are vague, almost dreamlike, and black and white, helping to set the eerie tone of the story and the fact that the book, the story Oli tells, is just that – a story in itself.

We are all stories.

Every chapter begins with a short dialogue between Oli and Eren, and these are set aside from the rest of the narrative, keeping the feeling of unease building as they hint at a missing piece of Oli’s story and Eren’s motivations.

In the same way that the book will envelope you as you read it, so Eren keeps drawing Oli back to him: even when the thought of the creature terrifies the boy, he keeps coming back. The fantasy of Eren’s stories is an addictive diversion from Oli’s own life, which is filled with stories far more stark and sombre. What is Oli’s mother keeping from him? Why does he get strange looks from people he doesn’t know as he wanders through this nowhere place, this small country town? Where is his dad?

To Oli, Eren is the fantastic, the unseen, the shadow lurking just out of sight – and he’s also his teacher and his escape. But at what cost?

As well as the spine-tinglingly sinister and ambiguous Eren, Oli meets Em and Takeru, a couple of local kids with their own stories and secrets. The interactions between the three are some of my favourite parts of Eren, and it is very interesting to read how the kids handle and react to the separate world of the grown-ups.

I would recommend this book in a heartbeat. If you like stories, fantasy, fairy tales and secrets, then pick up Eren – you won’t be disappointed.

Tell the story to its end.

I was sent a copy of this book in exchange for an honest review.

1

1

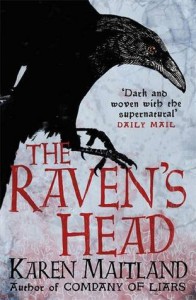

The Raven’s Head is a dark tale of secret rituals and black magic, and the children who get tangled up in an alchemist’s pursuit of the ultimate power…

This is the latest book from the author ofCompany of Liars, Karen Maitland. Like its precursors, The Raven’s Head is a historical novel, but with a good dose of the supernatural thrown in. It is dark and at times disturbing, and certainly not for the fainthearted.

On the whole, this is a very enjoyable read.

Maitland’s characterisation in particular is excellent, as she presents us with three main characters that differ from one another greatly but for each of whom we grow to care deeply. Wilky is a young boy who struggles to understand the strange and grown-up world unfurling around him; Vincent is a roguish youth who uses his wits to get by; andGisa is an apothecary’s assistant, clever and gentle. Each character’s story is told in a different voice and often a differing style – for example, Vincent’s parts are told in the first person and past tense, while both Gisa’s and Wilky’s are in the third person and present tense – which really helps to cement their personalities in your mind.

The story follows each character as they make their way unknowingly towards a mutual destination and mortal danger, where twisted minds work to interpret a holy book and unlock the secrets of life itself in the most deranged way imaginable. And it does get rather gruesome at times.

I thoroughly enjoyed the journey through the book, but was a little disappointed with the ending – or, specifically, the last few chapters that make up the epilogue – although I shan’t go into too much detail for fear of giving anything away. Let me just say that it felt inadequate following a carefully crafted 400+ page book and, in my opinion, would have flown a lot better had it been executed with greater subtlety. As it is, it reads more like the conclusion of a short story than a lengthy novel.

However, I would still recommend the book as the journey through it is very enjoyable, not to mention dark, fantastic and fun. Vincent’s voice and character were things that I particularly loved.

Pick up The Raven’s Head if you’re in the mood for some dark fantasy, but be prepared for a bit of gore and genuine nastiness!

I received a free uncorrected proof copy of the book from Goodreads Giveaways.

1

1

The Boy Who Lost Fairyland by Catherynne Valente

This book is utter nonsense… you’re going to love it.

Let me first say that Catherynne Valente has more imagination in one fingernail than most people do in their whole body. You can just imagine her as a hyperactive, hyper-creative kid who’s just seen Fairyland and wants to tell you all about it and she can’t wait for even one minute, no she can’t. It’s the sheer volume of words and references and, frequently, nonsense that hurtles at you like the cascade of a waterfall that you couldn’t stem if you jammed all your arms and legs into it.

At the start it feels a lot like that – that is, overwhelming and a bit like paddling against a commanding torrent of colours and lovely words and fantastic items that leaves you with very little room to breathe, much less grab hold of a tree branch for long enough to get your bearings. (The branch would probably turn out to be a boa constrictor, anyway.) But after a chapter or so you get into the swing of things, pick up a few native words and shrug on an ethnic jacket; you learn how to salmon upstream. And it’s easy, mad riding the rest of the way.

The story begins when a young troll by the name of Hawthorn is spirited away by the Red Wind and her Panther of Rough Storms and sent into the human world as a Changeling – an out-of-place little mischievous creature that is, for all intents and purposes, anarchy incarnate.

But of course, this isn’t actually where the story begins.

The Boy Who Lost Fairyland is the fourth in the Fairyland series and, while it can stand independently, much like a small child, it would be much better off being supported on one side or the other by its mum or one of its older siblings. That is to say: alone it is very good, but in line with its forerunners it would be glorious. I say this having not read the others, mind – it’s just that, towards the end of the book in particular, characters from the other books are mentioned and I think you’d enjoy these mentionings more if you had the faintest idea of who they were on about. The beginning of the book, too, launches confidently into an assertive stride and you can immediately feel the presence of the narrative stepping stones that led to this one.

After Hawthorn is recast as a small human child, he is completely and utterly confused and crestfallen. The oven and the chandelier won’t speak to him, his mother (who is clearly a witch) makes him toys that won’t come alive, try as Hawthorn might, and his father is quick to point out that he isn’t normal. But life must go on and our small troll with it, and so Hawthorn grows into a human boy: Thomas Rood. Along the way are the hurdles of school and other kids and being normal, and Thomas must do his best to fit in even as he forgets all about his real heritage. That is, until one day, when a carefully orchestrated (and not entirely normal) accident changes everything and stirs awake the troll deep inside…

Thomas did not have any clear idea what Normal meant, except that it was something Gwendolyn and Nicholas were, and Mysterious Unnamed Other Children were, and possibly Grocers and Teachers and Street Sweepers as well, but that Thomas was not. Despite the awful hurt that capital N did to his raw, naked heart, Thomas was still a little boy – at least, mostly a little boy – and he did not like his father to be sour. He began to collect Normals, so that he could identify them on sight.

The book is absolutely wonderful and incredibly creative, entirely comfortable in its well-worn fantastical shoes. It also often reminded me of Dianna Wynne Jones’s work (which is a great compliment as she is one of my favourite writers) in the way that it followed its protagonist around and, again, in the cameos of old favourites towards the end of the book, much like Howl’s resurgence in Castle in the Air (and I shan’t say more about that, only that you must read Howl’s Moving Castle if you haven’t already!). Another similarity is the use of illustrations and a brief summary of the upcoming adventure at the head of each chapter in the form of, for example, ‘Chapter 1: Entrance, on a Panther. In Which a Boy Named Hawthorn Is Spirited Off by Means of a Panther, Learns the Rules of the World, and Performs an Unlikely Feat of Gardening’ – a style that I absolutely adore.

The Boy Who Lost Fairyland is an extraordinarily fantastic book, rivalling Alice in Wonderland in nonsensicality and Howl’s Moving Castle in poise; get this book if you are a fan of either. Perfect for humans, trolls and fetches of all ages (ok, maybe ten and up, give or take). I will be picking up The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making, the first in the Fairyland series, sometime rather shortly.

I was sent an ARC copy of this book for review purposes. All opinions are my own.

'Wake', a new sci-fi/horror from Elizabeth Knox

Wake is a sci-fi survivor story that follows a group of people who suddenly find themselves in a living hell. Isolated from the rest of the world by a strange, hazy force field, the group must learn to survive in the aftermath of a murderous frenzy, in the prison of a ghost town that conceals a deadly secret…

Read through full review on my blog!